Mutual information¶

The intensity  of a voxel located at coordinates

(

of a voxel located at coordinates

( ) within the fixed image

) within the fixed image  is given

by:

is given

by:

and similarly, the intensity  of a voxel at coordinates

(

of a voxel at coordinates

( ) within the moving image

) within the moving image  is given

by:

is given

by:

We want to apply a coordinate transform

to the moving image such that it

registers best with the fixed image

to the moving image such that it

registers best with the fixed image  . However, since

. However, since

and

and  could have been obtained from different

imaging modalities, we cannot simply minimize the error between

intensities

could have been obtained from different

imaging modalities, we cannot simply minimize the error between

intensities  and

and  . Instead, we must attempt

to maximize the amount of information shared between the two

images. The statistical Mutual Information can therefore be

used as a similarity metric:

. Instead, we must attempt

to maximize the amount of information shared between the two

images. The statistical Mutual Information can therefore be

used as a similarity metric:

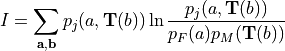

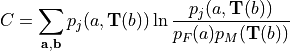

(1)¶

which depends on the probability distributions of the voxel

intensities for the static and moving images. We now view

and

and  as random variables with associated

probability distribution functions

as random variables with associated

probability distribution functions  and

and

and joint probability

and joint probability  . Note

that applying the spatial transformation

. Note

that applying the spatial transformation  to

to

will result in modification of

will result in modification of  . This

effect is implied with the notation

. This

effect is implied with the notation  .

Furthermore, if

.

Furthermore, if  results in voxels being

displaced outside of the image,

results in voxels being

displaced outside of the image,  will change.

Perhaps more importantly, if

will change.

Perhaps more importantly, if  results in a

voxel being remapped to a location that falls between points on the

voxel grid, some form of interpolation must be employed to obtain

results in a

voxel being remapped to a location that falls between points on the

voxel grid, some form of interpolation must be employed to obtain

, which will modify

, which will modify  . These effects are

implied with the notation

. These effects are

implied with the notation  .

.

The method of interpolation used to obtain  given

given

is important both in terms of

execution speed and solution convergence. Here we will discuss the

Partial Volume Interpolation method proposed by Maes et. al.

is important both in terms of

execution speed and solution convergence. Here we will discuss the

Partial Volume Interpolation method proposed by Maes et. al.

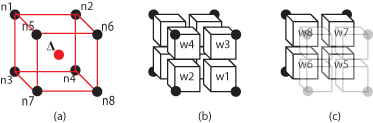

Figure 1(a) depicts the situation where  has displaced a voxel (red) to the center of a

neighborhood of 8 other voxels (black). The interpolation method divides the

volume defined by the 8-nearest neighbors (red) into 8 partial volumes (w1 -

w8) that all share the red voxel’s location as a common vertex Figure 1(b-c).

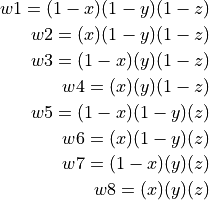

We can more formally define the 8 partial volumes as a function of

has displaced a voxel (red) to the center of a

neighborhood of 8 other voxels (black). The interpolation method divides the

volume defined by the 8-nearest neighbors (red) into 8 partial volumes (w1 -

w8) that all share the red voxel’s location as a common vertex Figure 1(b-c).

We can more formally define the 8 partial volumes as a function of

:

:

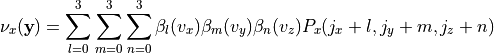

(2)¶

Noting that

Once the partial volumes have been computed, they are placed into

the histograms of their corresponding voxels in the 8-neighborhood.

Partial volume  is placed into the histogram bin

associated with

is placed into the histogram bin

associated with  ,

,  with

with  , etc.

This method is used in computing both

, etc.

This method is used in computing both  and

and  .

.

We now have a complete expression for the mutual information similarity metric, which we will use as a cost function that describes the quality of the registration.

(3)¶

We can attempt to achieve the optimal registration by maximizing this cost

function, which is achieved through modification of the coordinate

transformation  applied to the moving image

applied to the moving image

. It is important to note that the

. It is important to note that the  could be any

type of conceivable coordinate transformation. For example,

could be any

type of conceivable coordinate transformation. For example,

could represent a set of affine transforms to be applied

to the moving image. Here, however, we will be focusing on a parametrically

defined nonrigid coordinate transformation. The transformation

could represent a set of affine transforms to be applied

to the moving image. Here, however, we will be focusing on a parametrically

defined nonrigid coordinate transformation. The transformation

is characterized by the displacement field

is characterized by the displacement field

, which defines how individual voxels within the moving image

, which defines how individual voxels within the moving image

should be displaced such that

should be displaced such that  and

and  are

optimally registered. This displacement field is computed at every voxel

given the B-spline coefficients

are

optimally registered. This displacement field is computed at every voxel

given the B-spline coefficients  defined for the sparse array of

control-points:

defined for the sparse array of

control-points:

(4)¶

where ( ) form the indices of the 64 control points

in the immediate vicinity of a voxel located at

(

) form the indices of the 64 control points

in the immediate vicinity of a voxel located at

( ). Note, (

). Note, ( ) forms the

voxel’s offsets within the region bound by the 8 control-points in

the immediate vicinity of the voxel. For simplicity, we refer to

such a region as a tile.

) forms the

voxel’s offsets within the region bound by the 8 control-points in

the immediate vicinity of the voxel. For simplicity, we refer to

such a region as a tile.

Having defined the coordinate transformation

in terms of the B-spline

coefficients

in terms of the B-spline

coefficients  , it is becomes apparent that the mutual

information may be maximized through optimization of

, it is becomes apparent that the mutual

information may be maximized through optimization of  .

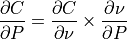

If this is to be accomplished via the method of gradient descent,

an analytic expression for the gradient

.

If this is to be accomplished via the method of gradient descent,

an analytic expression for the gradient

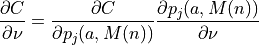

must be derived. The chain rule

is employed to separate the expression into two partial derivatives

with the first being dependent on the similarity metric employed

and the second on the type of transform employed:

must be derived. The chain rule

is employed to separate the expression into two partial derivatives

with the first being dependent on the similarity metric employed

and the second on the type of transform employed:

(5)¶

where the second term is easily obtained by taking the derivative

of (4) with respect to  :

:

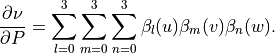

Referring again to the first term of (5), it is

important to realize that  and

and  are coupled

through the probability distribution

are coupled

through the probability distribution  and are

therefore directly affected by the 8 neighborhood partial volume

interpolation. This becomes further apparent when

and are

therefore directly affected by the 8 neighborhood partial volume

interpolation. This becomes further apparent when

is further decomposed:

is further decomposed:

(6)¶

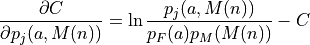

where the first term may be found by taking the derivative of

(3) with respect to the joint distribution  :

:

(7)¶

see {A}.

The second term,  ,

describes how the joint distribution changes with the vector field.

Explicitly stated, a displacement vector locally transforms the

coordinates of a voxel in the moving image

,

describes how the joint distribution changes with the vector field.

Explicitly stated, a displacement vector locally transforms the

coordinates of a voxel in the moving image  such that:

such that:

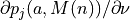

From Figure fig:pv8 it becomes immediately apparent that as the vector field is

modified the partial volumes  -

-  to be inserted into

the moving and joint histograms

to be inserted into

the moving and joint histograms  and

and  will change in

size. Consequently,

will change in

size. Consequently,  can be

found for

can be

found for  by taking the derivative of (2)

with respect to each of the Cartesian directions.

by taking the derivative of (2)

with respect to each of the Cartesian directions.

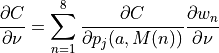

Therefore, as prescribed by (6), computing  at a given voxel in

at a given voxel in  involves first cycling through the

8-bins corresponding to the 8 nearest neighbors used during the partial volume

interpolation and computing

involves first cycling through the

8-bins corresponding to the 8 nearest neighbors used during the partial volume

interpolation and computing  for each, which

is scalar and therefore the same for all Cartesian directions. The 8

for each, which

is scalar and therefore the same for all Cartesian directions. The 8

values are each weighted by one

values are each weighted by one

. Finally, once this process has been

completed for all 8 bins, the resulting

. Finally, once this process has been

completed for all 8 bins, the resulting  values is assimilated into the sparse coefficient array

values is assimilated into the sparse coefficient array  by way of

(5). Once this is completed for all voxels, the next optimizer

iteration begins and the process is repeated with a modified coefficient array

by way of

(5). Once this is completed for all voxels, the next optimizer

iteration begins and the process is repeated with a modified coefficient array

.

.

NOTE

It is important to note that if all 8 histograms associated with

the neighborhood are equal, the value of

. This is a direct result

of

. This is a direct result

of

and similarly for the  - and

- and  -directions. However, when

the 8 histograms within the neighborhood are not equal, this will result in the

gradient

-directions. However, when

the 8 histograms within the neighborhood are not equal, this will result in the

gradient  being “pulled” in the Cartesian

direction of voxels associated with large

being “pulled” in the Cartesian

direction of voxels associated with large  ,

which is desirable when attempting to maximize MI.

,

which is desirable when attempting to maximize MI.